When we talk about stretching, mobility and flexibility, the terminology can get real confusing, real quick.

‘Passive stretching’, ‘active flexibility’, ‘active stretching’… these words are flung around like poop in a monkey enclosure at Chester Zoo.

So, to avoid confusion, for the purpose of this article:

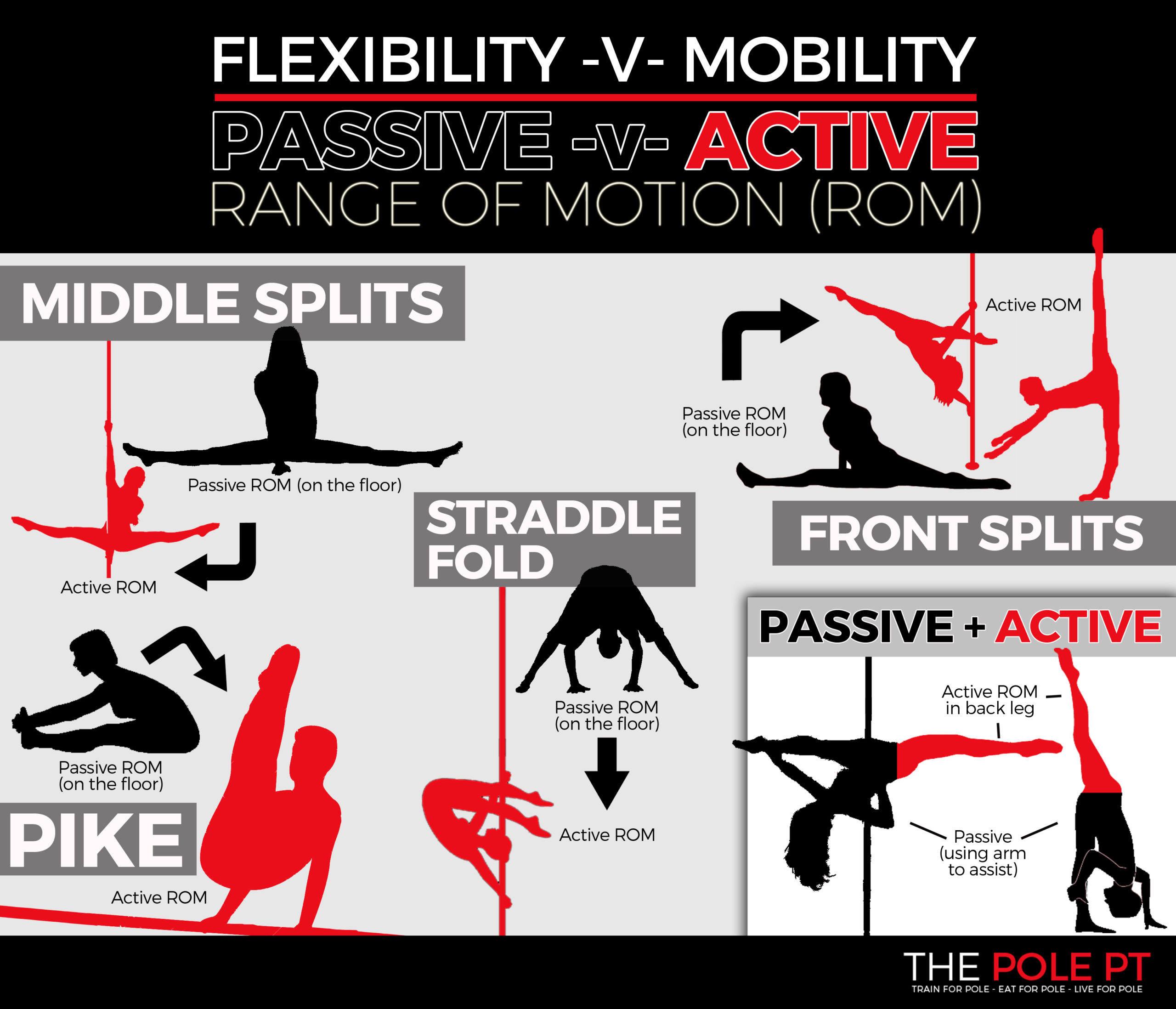

When I say ‘passive flexibility (or passive range of motion)’, I mean the range of motion you can access when you use something – maybe a hand, a partner, the floor, a strap or a prop – to help you into a stretch. For example, using a partner in a partner assisted stretch or using the floor to assist you to get into a deeper forward fold will demonstrate your passive hamstring flexibility.

When I say ‘active flexibility (or active range of motion / mobility)’, I mean the functional range of motion you can access without external assistance. This is based on movement and control; your ability to get your body into a position without needing to use outside force – ie without a wall, a strap, a pole or a hand to pull you into it.

To continue the example above, to demonstrate your active hamstring flexibility, that might be how far you can get your straight leg towards your chest in a seated position, without using your hand to pull it towards you.

Some people refer to this as ‘mobility’ (and to ‘passive flexibility’ as just ‘flexibility’), but hey, it’s semantics. We’re all talking about the same thing!

Like most things in life, it’s best explained with an infographic. I bloody love an infographic.

Active v passive range of motion

Now we’ve got that sorted, let’s look at the problem with passive flexibility in pole.

You’ve been diligently incorporating all those lovely split stretches into your training and propping your leg up on any available surface at every opportunity. I know the drill— you’re waiting for the kettle to boil in the staff room, leg casually extended on the worktop and Barbara from accounting comes in looking more confused and irked than ever. It’s for the splits gains, Barbara, deal with it.

But that passive flexibility you’ve been working so hard on won’t necessarily transfer seamlessly to the pole.

The ability to do a flat pancake stretch on the floor (a seated forward fold with legs straddled and chest to floor) means you have some impressive flexibility, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be able to see your Pleasers fly past your head in a straddle move on the pole, Cleo the Hurricane style.

And getting touch down on your front splits doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be able to get that back leg flat in your Jade.

Both of those stretches—pancake and splits—look impressive on photographs, but take away the resistance of the floor, and all of a sudden, your flexibility is a little less Instagram-able.

Let’s look at the Jade as an example. On the pole, you can pull the front leg with your hand (so you’ll get it straight if you have good passive range of motion in your hamstring), but your back leg has no floor to push against. You need to use your muscles to get it straight (this is where you need good active range of motion).

Strengthen what you stretch!

I’m not saying passive flexibility is pointless. Far from it. If you can’t get passively into a position, you sure as hell ain’t gonna be able to get into that position without assistance.

Passive stretching is great to get the body used to being in a new range of motion. You’re sending signals to your brain to say “hey, I’m okay here, we’re not gonna break, we got this”, and bit by bit, your body and brain will allow you to reach further into those positions. But at the same time as stretching, you should also be working on actively accessing that range of motion without assistance to strengthen the muscles at the same time.

Why?

Building strength around the joints, tendons and ligaments to support you in the increased range of motion you are building with your passive stretching will not only mean you can transfer those flexi moves onto the pole more easily, but also more safely.

Regular and intense passive stretching in the absence of strength work will increase your susceptibility to injury. Getting into that Bendy Kate chest stand might look cool for a photoshoot, but it really isn’t worth tearing a ligament or tendon for, trust me.

This balance of stretch v strength (passive v active) is even more important for those with hypermobility and those working on oversplits and other advanced contortion stretches.

Actively working in your full range of motion also means your body will be more prepared if things go wrong. If you don’t quite nail that Spatchcock and end up putting your joints into a temporarily strange and wonky place, the stronger you are in those end of range positions, the better your body will cope with those inevitable pole fails.

How to strengthen what you stretch and improve active flexibility

So you know that you should be aiming to balance your (passive) flexibility training with active flexibility – i.e. building strength and mobility, “but how?” I hear you cry!

This looks different for everyone and depends which muscle groups you are working on but look at it this way…

Your passive range of motion will determine how far you could potentially go using active range of motion. Most people (myself included) have a huge gap that can be bridged between their passive and active range of motion.

In the most basic terms, you just need to add some simple movements where you are actively using your end range of motion – that usually looks like a combination of: isometric holds in your end range; eccentric movements where you’re slowly moving into that end range; as well as more general movements into and out of that range.

Take home: If you work on actively moving in your full range of motion, you’ll be able to strengthen that passive flexibility you’ve been working on and convert it into functional mobility on the pole— and you’ll be a much safer, much stronger poler as a result.